Toronto’s Aga Khan Museum Creates a Space of Healing With Afghanistan My Love Exhibition

“These works are the voice of the Afghan people—it is what people on the ground are thinking and feeling,” curator Marianne Fenton says. “It’s the sense of relief in seeing your concerns highlighted somewhere that's visible.”

I See You, print by ArtLords. Photo by Aly Manji.

Visitors are met by a pair of large, haunting brown eyes upon entering the Aga Khan Museum’s Afghanistan My Love exhibition. They belong to a young Sikh girl, the focus of one of ArtLords‘ best-known works, I See You, one of the Kabul-based collective’s many public murals in Afghanistan. The watchful gaze acts as a whistle blower on corruption, with the original painted on a blast wall surrounding the Afghan intelligence agency.

The assemblage of murals, paintings, and multimedia works that form this new exhibition, which runs until April 10, 2023, are symbols of protest and solidarity. They’re a means of filling a cultural gap in a country fractured by war, and to which many Afghan artists no longer have access.

While creative freedom briefly flourished in Afghanistan during the 20-year U.S. occupation, the resurgence of the Taliban regime’s iconoclasm has meant ArtLords have seen many of their public murals—over 2,000 across the country—painted over. “This approach of erasure of imagery feeds into erasure of culture—images are culture,” says Shaheer Zazai, whose kaleidoscopic pieces bookend the exhibit. Zazai, who was born in Afghanistan but now calls Toronto home, explores cultural identity as an Afghan living in diaspora.

Museum visitors paint part of the ArtLords communal mural at the Aga Khan Museum. Photo by Salina Kassam.

Shaheer Zazai’s Blackout series. Photo by Alnoor Meralli.

Final design for ArtLords x Aga Khan communal mural. Photo courtesy of Aga Khan Museum.

Established in 2014, ArtLords emerged as a dissident voice in the country, using murals as canvases to express the anxieties of the communities they work in and promote messages of peace and human rights. Often, the public would be invited to help create the paintings, offering a sense of catharsis in an otherwise tumultuous time. “These works are the voice of the Afghan people; it is what people on the ground are thinking and feeling,” curator Marianne Fenton says. “It’s the sense of relief in seeing your concerns highlighted somewhere that’s visible.”

Mirroring the collaborative murals created in their home country, ArtLords worked with the Aga Khan Museum to create an oversized communal mural that museum visitors can help paint throughout November. It explores the experience of carrying your culture and identity with you into a new country, as well as tethering the losses of both Afghanistan and Canada during war. An Afghan girl carrying a map of Afghanistan under her arm is set against the backdrop of Canada’s Rocky Mountains, and red poppies bloom against the Buddhas of Bamiyan.

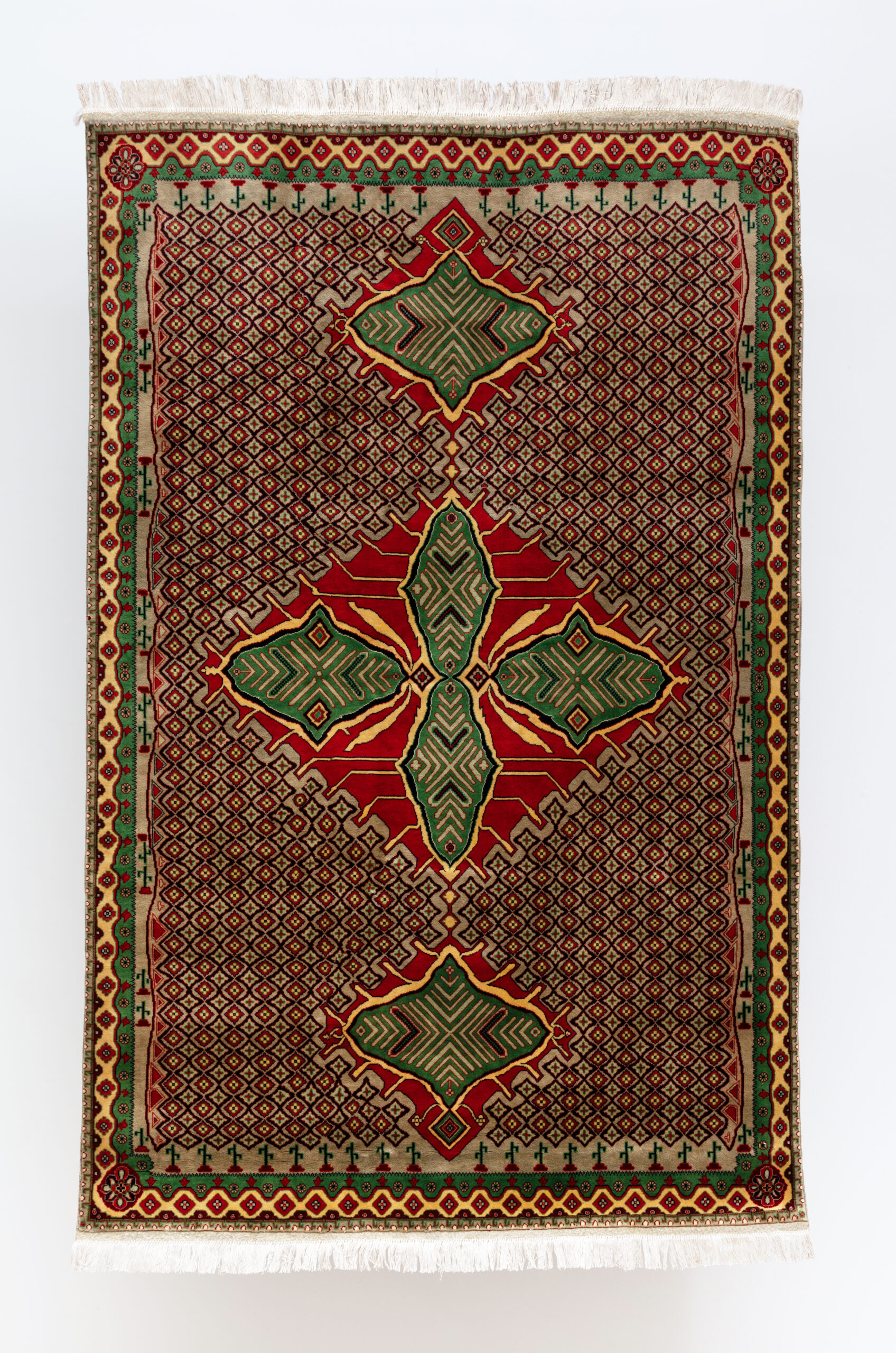

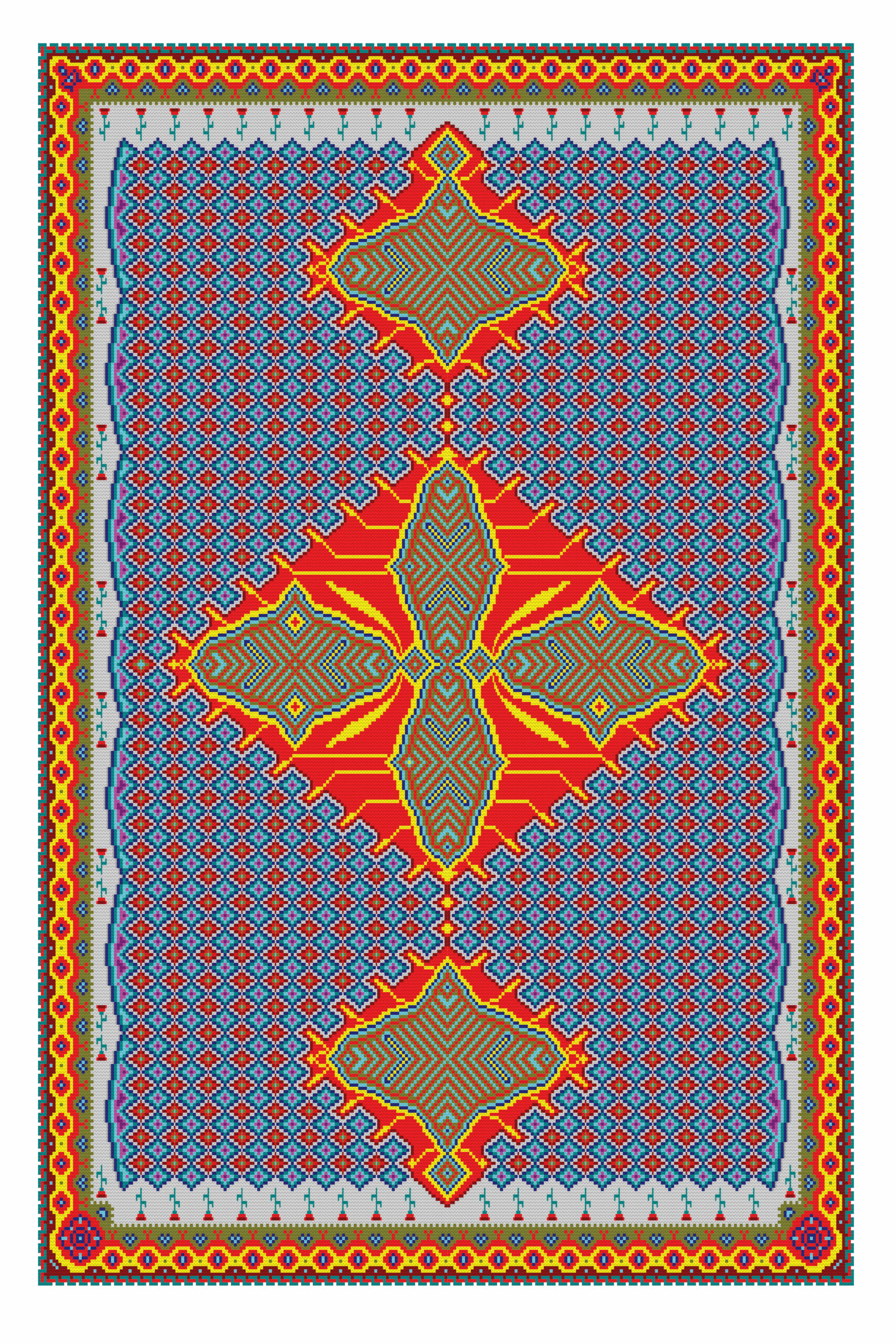

Zazai explores a shifting concept of identity in his work A Call Home, a series of carpets he designed using Microsoft Word, which were then brought to life by traditional weavers in Afghanistan. Inherent in the title is a sense of longing for things lost across time and distance. “The strangest thing about working in relation to cultural identity for me is not having the option to visit the country and reengage with it,” Zazai says. “It’s like explaining something you don’t fully understand yourself.”

A Call Home by Shaheer Zazai at the Aga Khan. Photo by Aly Manji.

By leaving the designs in the hands of the weavers, small elements and colours were added or changed. “I sent an image home, and in response I got the carpets. It’s almost like they sent me something to decipher,” Zazai says. The carpets arrived in Toronto in July 2021, a month before the Taliban took control of Afghanistan, at which point Zazai created a series of sombre prints comprising white text on a black background entitled Blackout, which accompany A Call Home. “I couldn’t create in colour at that point,” he explains.

One of these works, Bagh-e-Babur, depicts an important Mughal garden in the heart of Kabul (the site has pending UNESCO World Heritage status) that has acted as a gathering place in the city for centuries, offering a meditation on the connection between people and place, and what happens when this is broken. But there is something hopeful to be found in it as well: the regeneration embodied by gardens.

This work, together with five small colourful works at the beginning of the exhibit that the viewer is meant to turn around and witness once again before exiting, evoke possibility. “It’s unbelievable that hope can exist in Afghanistan, and it speaks to the resilience of the population,” Zazai says. “We can only hope for a brighter future.”